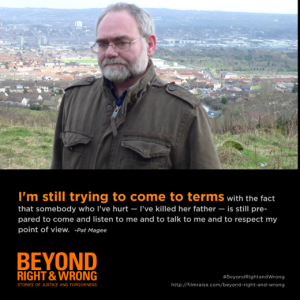

Dr. Patrick Magee

I was released from prison in 1999, having served 14 years under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. Whilst in prison I completed a PhD examining the representation of Irish Republicans in ‘Troubles’ fiction .

I was released from prison in 1999, having served 14 years under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. Whilst in prison I completed a PhD examining the representation of Irish Republicans in ‘Troubles’ fiction .

It was important for me as part of the peace process in North of Ireland to recognise that now we should engage with former enemies and political opponents, addressing the needs and grievances of victims, helping to break down differences by explaining ourselves to the other.

For 27 years I was a committed member of the IRA, whether on active service, on the run or in prison. I spent a total of 17 years either interned or sentenced because of my involvement. For Irish republicans prison was another war-front and we resisted all attempts to criminalise us and what from our perspective was a legitimate resistance struggle. We believed that armed struggle against a powerful enemy was legitimate because no other options were open to us other than to defend our communities against state oppression.

I was released on license from life imprisonment in 1999 under the terms of the Belfast Agreement, a political compromise achieved after decades of violence which held and continues to hold the hope that political progress is achievable through purely open, democratic, constitutional means. In this new political dispensation the legacy of the conflict could now be addressed, in terms of the many outstanding issues and grievances needing resolution if we are all to move on and build a peaceful future together.

A crucial part of that legacy is the need to look back over the conflict and to understand it in terms of the many conflicting perspectives. That will entail ensuring that many voices previously excluded or misrepresented must now be heard, including the voices of the victims. In that light, as an individual, I agreed to meet Jo. Her father, Sir Anthony Berry had been killed, along with four others, in the IRA’s attack on the Grand Hotel. I had planted the bomb.

So, on the day, I was there to explain, in essence to justify, the armed struggle; and specifically ‘Why Brighton’. I was wearing a political hat. We talked for three hours. But something happened during that first encounter.

Jo’s openness, calmness; her apparent lack of hostility – in fact her willingness to listen and to try to understand, disarmed me. Had Jo instead shown anger, however justifiable, it would for me have been easier to cope with. The political hat would have remained firmly attached. But in the presence of such composure and decency, as I said, I felt disarmed. It was a cathartic moment. It didn’t matter that as a former member of the IRA I could politically justify my past actions in terms of the legitimacy of the struggle. As an individual I carried the heavy weight of knowing I had caused profound hurt to this woman. I expressed a need to really hear what she had to say and to help her come to terms with her loss, if that were possible:

‘I want to hear your anger, to hear your pain.’

A political obligation henceforth became a personal obligation. I now realised more fully that I was guilty of something I had attributed to the other: that our enemies demonised, dehumanised, marginalised, reduced us. I began from that moment to see Jo’s father in a fuller light and to begin the process of understanding his view. I was also guilty of adhering to a reduced view and of not perceiving the other’s full humanity; instead apprehending our enemies in terms of their uniform or solely from their political colours. All that I came to admire and respect in Jo was surely due in part to his gift of values so apparent in her. And that was a measure of the loss. Jo’s loss of her father; her daughters’ loss of a grandfather. But loss also in terms of my own humanity. For war does rob combatants of something of what it is to be human, of an essential capacity to empathise and to see the world through the eyes of others. As a consequence, therefore, of this moment of insight, what began as a perhaps one-off encounter became a process of further meetings.

In agreeing to meet me that first occasion and in continuing to meet me she has demonstrated a truly admirable, strength and purpose in her endeavour to try to make sense of her loss and her preparedness to listen to my perspective.

Incredibly we have met over 100 occasions since that first time in November 2000, addressing various audiences like this, attending conferences in Ireland, Britain and internationally; speaking at universities and schools, doing media work and collaborating on documentaries, talking to a wide range of people: victims, former combatants, community workers, police personnel, prisoners and prison staff. Now we are writing a book together.

After one of our earliest meetings, Jo told me that her daughter had asked:

‘Was I sorry’ to which Jo replied ‘Yes’ and then Jo’s daughter said,

‘Does this mean that Granddad Tony can come back now?’

Out of the mouths of children!

No matter what we can achieve as two human beings meeting after a terrible event, the loss remains. Neither forgiveness nor understanding can fully embrace that loss. The hope lies in the fact we continue to meet in order to further this mutual process towards understanding.